Fatal outcomes in elderly patients after COVID-19 vaccination

In the period 27 December 2020 to 15 February 2021, about 29 400 of Norway's nursing home patients (aged 61–103) were vaccinated with the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2. During the same period, the Norwegian Medicines Agency received 100 reports of suspected fatal adverse reactions to the vaccine. An expert group has examined the 100 reported deaths and concluded that 10 (10 %) are most likely related to the vaccine while there could be a possible link for other 26 individuals (26 %). A recent review of other 38 cases linking the COVID-19 vaccines and the death found the following causes of death: vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) (32), myocarditis (3), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) (1), myocardial infarction (1), and rhabdomyolysis (1). More than half of these cases were in elderly individuals. Unfortunately, there were only a few publications on postmortem diagnostics of adverse events linked to vaccination. Here are 7 brief medical case reports.

An 85-year-old Caucasian woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, hyperlipidemia, and asthma who was diagnosed with a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) two months prior, came to the emergency room two days after receiving the second dose of the MODERNA COVID-19 vaccine with generalized weakness, muscle cramps, and loss of appetite. The patient started to feel weak the same afternoon after receiving the second dose. Later, she went to use the bathroom and could not stand up from the toilet seat. The patient completely lost her appetite and experienced nausea, without any vomiting/diarrhea. The next day, her weakness worsened along with abdominal and muscle cramps, and she was brought to the ER by ambulance. Family history was positive for autoimmune disease in maternal grandmother, supporting the possibility that autoimmunity is a major risk factor for covid vaccine-related rhabdomyolysis. Over the course of hospitalization, the patient became progressively weaker to a point where she could not even lift/move her hands or legs. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, initially on bilevel positive airway pressure/intermittent high-flow oxygen, but later intubated on ventilator support. The patient ultimately had a cardiac arrest, was terminally extubated and died the same day. A similar but non-fatal case in a 30-year old woman (after Moderna vaccine) was linked to her genetic polymorphism in RYR1 gene.

An elderly female resident of a nursing home in Germany received her initial vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 with Comirnaty®. She did not have any symptoms for two days, but three days later, she developed a fever. It was successfully managed with an antipyretic, but her general condition kept deteriorating. On the 5th day after the vaccination, she was found lifeless in her room. The forensic autopsy found the cause of death to be pulmonary artery embolism with infarction of the right lower lobe of the lung with deep leg vein thromboses on both sides.

A 63-year-old man, with a medical history including insulin-dependent type II diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease and atrial fibrillation, electively received a first dose of the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Twelve days later he presented to hospital with non-specific symptoms including vertigo, abdominal pain and fatigue. On admission, preliminary tests prompted a working diagnosis of ketoacidosis and silent myocardial infarction. In the first days after admission, he deteriorated neurologically, with declining

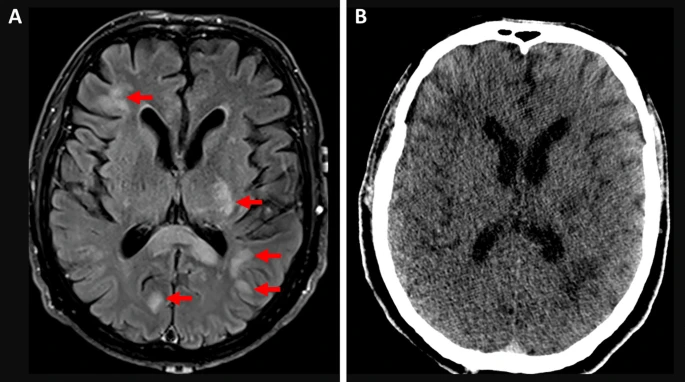

cognition, emerging disorientation and impaired attention. On day four, he suddenly became poorly responsive. Clinical tests led to a presumed diagnosis of encephalitis, and empiric antibiotics and antivirals were started. He was intubated the following day. Based on the radiological and histological findings, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) was diagnosed. Despite treatment with corticosteroids and plasmapheresis the patient failed to improve. He died on day 20 of admission. Similar but non-fatal cases were described for individuals in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s after the same AZD1222 vaccine or other mRNA and inactivated virus COVID-19 vaccines.A 69-year-old woman with arterial hypertension treated daily by hydrochlorothiazide and angiotensin receptor antagonist received a first dose of Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine. Eleven days after the vaccination, the patient developed headache associated with behavioral symptoms. At day 13, her daughter found her unconscious. Physical examination revealed a coma Glasgow 4/15, right mydriasis, bilateral Babinski reflex

without hemodynamic instability or respiratory failure. Immediate CT scan followed by MRI highlighted a severe bilateral frontal hemorrhage with brain herniation complicating a cerebral venous thrombosis of the left internal jugular vein, sigmoid sinus and superior sagittal sinus. Thoracic CT scan showed concomitant segmentary pulmonary embolism. Blood analysis at admission revealed an isolated thrombopenia measured at 18G/L with positive anti-PF4 antibodies. She was intubated, but evolution was dramatically poor in the next few hours with brain death, leading to an organ donation procedure.Postmortem investigations of 18 persons who deceased shortly after receiving a vaccination against COVID-19 included these cases:

69 year old male died at home from vaccine-triggered myocardial infraction on the 9th day after receiving his Johnson & Johnson vaccine (autopsy revealed vaccine-caused thrombosis, positive anti-PF4 heparin antibody, HIPA and PIPA tests),

65 year old male died at home one day after receiving the 1st dose of Comirnaty vaccine (BNT162b2, Pfizer). The cause of death was determined as vaccine-caused myocarditis. Autopsy revealed severe coronary sclerosis, massive cardiac hypertrophy, myocardial infarction scars and myocarditis. Anaphylaxis diagnostics was negative.

65-year-old male died in the hospital on the 10th day after receiving the 1st dose of Vaxzevria vaccine (AZD1222, Oxford–AstraZeneca). The cause of death was determined as vaccine-caused cerebral venous thrombosis and cerebral hemorrhage with hypoxic brain damage. Postmortem findings Signs of a bleeding diathesis, cerebral hemorrhages, CVT, mild coronary sclerosis, anti-PF4 heparin antibody tests: positive, HIPA-Test: positive, PIPA-Test: positive

All elderly individuals whose death was linked to the vaccine in this postmortem examination had preexisting cardiovascular diseases.

Many deaths were presumed to be unrelated to the vaccination. An 82-year-old male and another 91-year-old male both died next day after receiving their Spikevax vaccine (mRNA-1283, Moderna) and both were presumed to die because of pre-existing cardiological conditions. In both cases autopsy found severe coronary sclerosis, massive cardiac hypertrophy, and extensive myocardial infarction scars while anaphylaxis diagnostics was negative. Several cases of cerebral hemorrhage shortly after vaccination were also presumed to be not related to vaccination, if anaphylaxis and anti-Hepa antibody diagnostics were negative. Notable deaths argued to be unrelated to vaccination despite occurring weeks after it include 88-year-old baseball legend Hank Aaron (claim: unproven).

REFERENCES

Ajmera KM. Fatal case of rhabdomyolysis post-covid-19 vaccine. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2021;14:3929.

Permezel F, Borojevic B, Lau S, de Boer HH. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) following recent Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology. 2021 Nov 4:1-6.

Jamme M, Mosnino E, Hayon J, Franchineau G. Fatal cerebral venous sinus thrombosis after COVID-19 vaccination. Intensive Care Medicine. 2021 Jul 1:1.

Edler C, Klein A, Schröder AS, Sperhake JP, Ondruschka B. Deaths associated with newly launched SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (Comirnaty®). Legal Medicine. 2021 Jul 1;51:101895.

Maiese A, Baronti A, Manetti AC, Di Paolo M, Turillazzi E, Frati P, Fineschi V. Death after the Administration of COVID-19 Vaccines Approved by EMA: Has a Causal Relationship Been Demonstrated?. Vaccines. 2022 Feb;10(2):308.

Comments

Post a Comment